Review: Sounding Thunder

Because of the amount of contextual information, I think this book would be an ideal first dive into Ojibwe language literature for people who aren’t very familiar with Ojibwe culture and history.

This book is a bit different from the others I’ve read so far, and in some ways I think it would actually have made more sense to put it as the first book on the list.

The reason I say this is because unlike the other books I’ve read for this marathon, Sounding Thunder is probably 60% English text and 40% Ojibwe text with English translation. The Ojibwe sections are selections from author Brian McInnes’s conversations with his great-uncle and great-aunt, who were the children of famous WWI veteran Francis Pegahmagabow. The remaining English sections provide historical and cultural context for the Ojibwe stories. Because of the amount of contextual information, I think this book would be an ideal first dive into Ojibwe language literature for people who aren’t very familiar with Ojibwe culture and history.

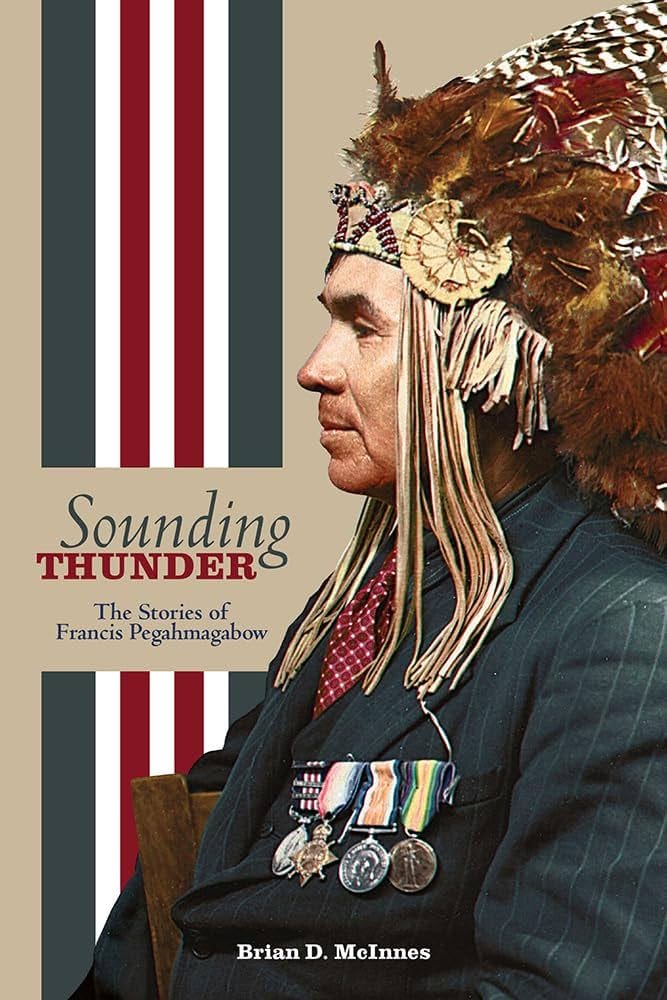

The content of the book is technically oriented around Francis Pegahmagabow’s life, but as McInnes indicates in the introduction, it is far from a typical biography. Instead, the book and the stories included within it aim to give a sense of the community within which Pegahmagabow lived, the cultural practices and beliefs he partook in, and what he was like as a father and relative.

My favorite section was the story of “Gchi-Ngig—The Giant Otter” and the explanation of it that follows in “Learning From Stories” (chapter 5). In that chapter, McInnes does a deep explanation of the story that precedes about the giant otter, Gchi-Ngig, examining its structure, plotline, characters, and even the use of topographical words in the story. Interestingly, he concludes that it fits uneasily between the two most well-known Ojibwe genres of dbaajmowin and aadsookaan. Although the storyteller uses the word dbaajmo to describe his telling, McInnes states that community members and elders he consulted with later told him it seemed to have more in common with aadsookaan structure.

I think this is a fascinating debate that speaks to a couple of things. First, I think even many of us who are fairly knowledgeable about Ojibwe literature are lacking a lot of knowledge about Ojibwe genre beyond dbaajmowin/aadsookaan, and I hope we can maybe investigate this further before elders who know these things pass away. Also, the categorization of this story reminds me of what I have said about previous stories in this marathon: that how we categorize things as spiritual or supernatural versus mundane has shifted, even for Ojibwe people. I personally think this story is really a dbaajmowin because it references specific people and occurred within almost-living memory (probably the 1860s, according to McInnes), but the idea of encountering a giant otter who smashes huge rocks is something that most of us don’t think of as part of an average human experience anymore. That said, I do think there are some really interesting things to be teased out regarding how dbaajmowinan and aadsookaanan do often resemble each other. I suspect our best storytellers draw upon aadsookaanan to tell their dbaajmowinan…but I digress.

I’ve talked so much about the English sections but I promise the Ojibwe sections are also really incredible. The story “Ndedem Gaa-Giiwed” about coming to terms with Francis Pegahmagabow’s death is beautifully told. The words we are left with at the end of the book, which were spoken by Francis’s widow Eva to her son, are some of my favorites:

“Dbiyiidog sa nii go ge-naabiwinen mii ji-waabmad Mnidoo.”

Wherever it is that you look you will see the Spirit.“Waawaaskones be-bimaajiiging—mii go ow,” kida.

”In the way that a flower grows there in front of you—that is the one,” she said.“Miinwaa gegoo mtigoons niw niibiishensan bmaasingin.”

“And again in the way the leaves of trees flutter in the wind.”“Mii go ow.”

That is the one.”“Gego memkaaj zhaaken namhew-gamgoong.”

“You don’t have to go to church.”“Mii go kina maa enaabiyin eyaamgak.”

“It is in everything that you look at.”“Miinwaa gegoo giiji-bmaadiz.”

“And also in your fellow human being.”“Mii go ow.”

“This is the one.”“Mnidoo.”

“The Spirit.”

(I’ve kept the format of interlinear translation with italicized Ojibwe as used in the book, even though it’s not my preference.)

The relationship between Ojibwe and Christian practices is actually also a recurring theme here, as Pegahmagabow was both Catholic and a follower of many traditional practices; Eva on the other hand wrote the words “I am a pagan” in a bible she was gifted! It offers a perspective on the relationship between Ojibwe and Christian spiritual practices that is rather different from Obizaan’s book, for example. Anyway, I think these words will look slightly trite to the English reader. But in the Ojibwe I find them very profound in ways that are hard to describe. I guess that’s just another motivation for people to read these in the original language!